Introduction

Unruh (2000) defined “carbon lock-in” as an industrial economy that perpetuates the use of fossil fuels due to the co-evolution and interdependence of technical systems, institutions and society (Technical-Institutional Complex). This promotes through mutual self-interest the status quo and inhibits the introduction of alternatives to fossil fuels. Seto et al. (2016) describes three types of carbon lock-in: infrastructural & technological, institutional and behavioural and are summarised in Table 1.

For detailed description of the concept of carbon lock-in resulting from the Technical Institutional Complex the reader is referred to Unruh (2000), Unruh (2002) and Seto et al. (2016).

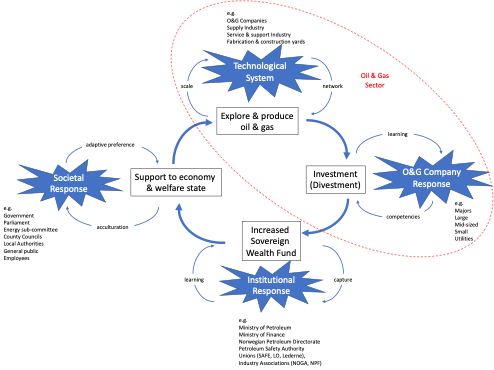

This briefing will explain how wealth generated by the Norwegian oil & gas (O&G) sector has led to carbon lock-in and how continued extraction of O&G is now a barrier to low-carbon business. The term “Petroleum-Institutional Complex” (PIC) is introduced.

Background

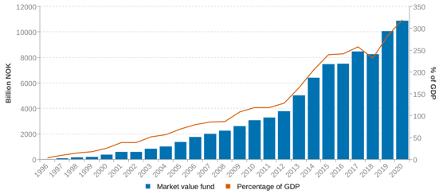

The discovery of the Ekofisk field in 1969 started the Norwegian O&G sector. Today, Norway is the world´s 15th largest oil and 3rd largest gas exporter representing ~2% and ~3% of global output respectively (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021a). Macro-economically, the sector accounts for 36% of exports, 10% of State revenues (GBP ~8.6 billion), 12% of GDP, 18% of total investments and employs, directly or indirectly, ~225,000 people (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021c, NPD, 2021b). Revenue from Norway´s O&G sector is a key part of fiscal policy underpinning State finances and is the basis for a sovereign wealth fund (SWF) worth GBP ~1 trillion or GBP 175k per registered person in Norway (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021d); Figure 1.

Norway has green credentials: 98% of domestic electricity generation is from renewables (Energy-Facts-Norway, 2021), domestic heating is from electricity and electric vehicle sales account for >50% of market share (Reuters, 2021). With respect to the O&G sector, Norway has a CO2 tax (1991) and EU-ETS (2007) making it the second most taxed sector in Norway after aviation (NPD, 2021b).

The Ministry of Petroleum & Energy (MPE) is responsible for policy/regulatory framework and the Norwegian Petroleum Directorate (NPD) has oversight for optimum resource management. Both Equinor and Petoro, large Norwegian O&G companies report to the MPE (the State being the majority owner); see Figure 2 for the organogram of Norwegian State institutions responsible for policy-making, regulation and oversight.

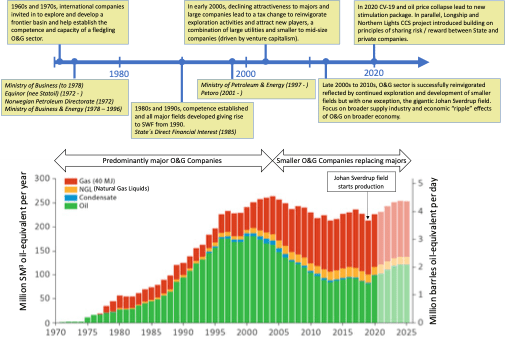

These institutions evolved in parallel with the O&G sector (Figure 3) with the founding principle to maximise value from the O&G sector for Norwegian society in a long-term perspective (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021b). Recently, however, following significant losses in Equinor´s business unit responsible for the USA (Adomaitis, 2021), oversight of Equinor, Petoro and SDFI[1] has been moved from the MPE to the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Fisheries (Nilsen et al., 2021) to address any potential conflicts of interest.

O&G companies pay 78% tax comprising company tax (22%) and special petroleum tax (56%); subsidies to incentivise investment include tax on net profit only with losses carried forward, short depreciation (6-years) with uplift and an exploration refund (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021e). The philosophy is for a neutral tax system that shares the risk/reward between companies and the State, maximising value creation for society and providing a predictable but not excessive rate of return for O&G companies (Osmundsen, 1999). In addition, policies limiting annual expenditure from the SWF to 3% of interest earnt has ensured that Norway has not suffered from the “resource curse” as seen in other countries (Holden, 2013).

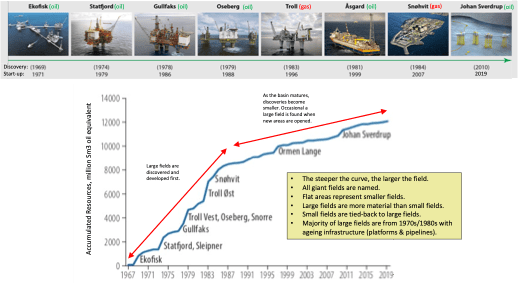

Thirty-nine O&G companies are currently active in Norway (NPD, 2021c). In 2004, a tax refund was introduced to revive exploration; companies only pay 22% of exploration costs and receive a 78% tax refund on the rest (NPD, 2021b). This change boosted the number of smaller companies and since 2004, these have replaced the large international O&G companies (majors); recent consolidation has given rise to medium-sized Norway-focussed companies (Figure 4). This transition reflects the creaming curve of O&G basins, where the largest most material fields are discovered first and thereafter materiality decreases as fields get smaller; smaller fields are less attractive to the majors who have higher internal rate of return hurdles compared to smaller companies (NPD, 2021b); Figure 5.

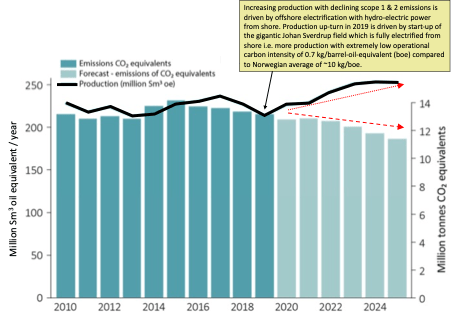

Emissions-wise, the O&G sector emitted ~13 Mt CO2e in 2019 and is the single largest source (28%) (Statistics Norway, 2020). The O&G sector plans to reduce operational carbon through increased efficiency and electrification of facilities with a goal to reduce from 13.7 to 6.75 Mt CO2e by 2030 (KonKraft, 2021); Figure 6. However, only scope 1 & 2 emissions are included while scope 3 emissions from exported O&G are not and amounted to ~677 Mt CO2e for 2020 assuming ~1.425 billion boe[1] exported in 2020 (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021a) @ 475kg CO2e/boe (Gordon and Feldman, 2016).

[1] Barrel-of-oil-equivalent

Barrier to a low-carbon future

Norway´s wealth is synonymous with the O&G sector (Norwegian Petroleum, 2021d). Early policies secured high income to the State, protected Norway from the “resource curse” and generated the world´s largest SWF. However, it is proposed that this success now impedes transition to a low-carbon economy as the incumbent PIC (O&G sector, government and societal institutions) is now locked into continued O&G production as it is a source of wealth for Norway (Figure 7).

Government policies in the 1960´s/1970´s shared the risk/reward in order to attract the majors to develop O&G resources and help establish technical competence and capability in Norway. As the sector matured in the 1980s/1990s, these policies were retained to address the cyclical (boom & bust) nature of the industry created by oil price volatility (Dahl et al., 2017) and temporarily updated in response to the Covid-19 pandemic (Reuters, 2020, Norwegian Petroleum, 2021e). It is inferred that declining materiality and the transition from the majors to smaller companies has reinforced the need to maintain tax subsidies; smaller companies lack the financial strength of the majors and require tax subsidies (lower costs) to secure funding from venture capitalists and banks (Venables, 2018, IEA, 2020).

The NPD, whose role is to maximise value creation from O&G extraction, actively promote exploration to offset declining production and recently stated that only 50% of O&G resources have been discovered and extracted to date (NPD, 2021a). This has created “exploration-only” companies attracted by the exploration tax refund and sustains technological and institutional lock-in of the PIC. Infrastructural lock-in has also arisen because existing O&G facilities are ageing and timely exploration is required to maximise O&G extraction and value creation before these facilities can no longer be used; smaller fields cannot support stand-alone capital investment. This lock-in is further reinforced by the fear of stranded assets, especially for smaller companies and their investors (Livsey, 2020).

The PIC narrative, dominated by references to value creation, long-term future, employment opportunities and economic ripple-effects, also presents “green” credentials of low operational carbon intensities for scopes 1 & 2 (KonKraft, 2020, KonKraft, 2021). The MPE have influenced these low-carbon efforts with policies that push for electrification of facilities (NPD, 2020) and state that continued extraction is justified to avoid carbon leakage to countries with higher carbon intensities perpetuating lock-in (NPD, 2021b). However, scope 3 emissions of exported O&G and the broader climatic implications are conveniently overlooked.

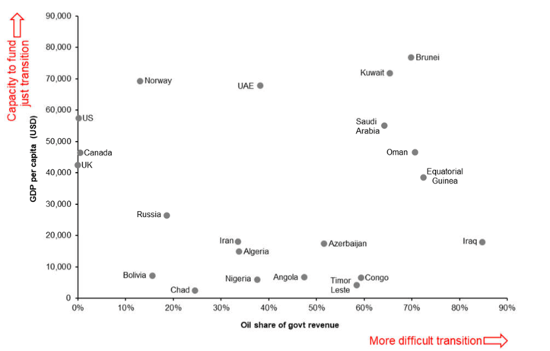

Fæhn et al. (2017), McKinnon et al. (2017) and Holtsmark (2019) propose that Norway is well placed to implement supply-side policies that could reduce scope 3 emissions. Muttitt & Kartha (2020) demonstrate that Norway is well positioned to play a leading role in a just energy transition with a high GDP per capita and low percentage of the share of government revenue coming from oil (Figure 8). Aune et al. (2020) highlight that stopping exploration activities in Norway, similar to other countries (Piggot et al., 2018), will have limited macro-economic impact due to a declining creaming-curve. Yet the NPD actively promotes the remaining resource potential (NPD, 2021b). Both Pye et al. (2020)and Pellegrini et al. (2021) discuss the need for equitable solutions for keeping unburnable O&G in the ground to limit global warming through supply-side policies. Norway, with its SWF, is ideally placed to lead, however, domestic policies are restricted to the demand-side (e.g. CO2 tax) to avoid the issue of market turmoil and vulnerability of smaller companies to stranded assets (Chevallier et al., 2021). It is ironic that the SWF was advised in 2018 to divest from O&G investments for this reason (Van der Ploeg, 2018) and did so by end 2020 (Arvin, 2021b).

Vergragt et al. (2011) argue that carbon capture and storage (CCS) reinforces fossil fuel lock-in and is perhaps epitomised by the Northern Lights part of the Longship CCS project: the objective to demonstrate commercial feasibility of sequestrating industrially-sourced CO2 using existing Norwegian O&G CCS experience (MPE, 2020).

Northern Lights is the storage element and mirrors the O&G sector in the 1970s; risk/reward is shared between the State and participating companies with the MPE/NPD responsible for regulation/oversight. The project makes use of existing competence in the O&G sector which is attractive to O&G employees, suppliers and unions. However, all these participants advocate continued extraction of O&G and cynically, CCS outwardly solves/distracts from the issue of scope 3 emissions. This can be explained as the PIC´s inbuilt response to maintain the system for mutual benefit by developing common interests to allow continued O&G extraction (Unruh, 2000, Seto et al., 2016). Arvin (2021a) proposes that separation of economic from climate policies is the cause i.e. the O&G economy that underpins policy has successfully externalised the impact of scope 3 emissions whilst promoting reductions in scopes 1 & 2 and carbon leakage to justify continued extraction.

Summary

Kenner and Heede (2021) leave no doubt that O&G companies will not lead efforts to decarbonise and draw similar conclusions to Abreu et al. (2020) in that policy makers will need to take the lead. However, it is argued that Norwegian policy-makers are impeded by carbon lock-in from the PIC which now act as a barrier to low-carbon business.

Unruh (2002) states that external factors are required to help policy-makers escape from carbon lock-in. Norway has avoided the “resource curse” but is now affected by “resource inertia” and given the low interest in the energy transition from the general public (Tvinnereim et al., 2020), policy-maker procrastination towards low-carbon business will continue.

References

ABREU, M. C. S. D., WEBB, K., ARAÚJO, F. S. M. & CAVALCANTE, J. P. L. 2020. From “business as usual” to tackling climate change: Exploring factors affecting low-carbon decision-making in the Canadian oil and gas sector. Energy Policy,148.

ADOMAITIS, N. 2021. Equinor sells U.S. Bakken shale assets, posts record loss for 2020 | Reuters [Online]. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-equinor-usa-idUSKBN2AA0FX: Reuters. [Accessed 10th February 2021].

ARVIN, J. 2021a. How Norway’s oil and gas legacy complicates its climate change leadership. VOX [Online]. Available: https://www.vox.com/22227063/norway-oil-gas-climate-change [Accessed 20th February 2021].

ARVIN, J. 2021b. Norway’s trillion-dollar wealth fund sold the last of its investments in fossil fuel companies. VOX [Online]. Available: https://www.vox.com/22256192/norway-oil-gas-investments-fossil-fuel [Accessed 20th May 2021].

AUNE, F. R., CAPPELAN, Å. & MÆLAND, S. 2020. Konsekvenser av redusert petroleumsvirksomhet (Consequences of Reduced Petroleum Activity). Statistisk sentralbyrå.

CHEVALLIER, J., GOUTTE, S., JI, Q. & GUESMI, K. 2021. Green finance and the restructuring of the oil-gas-coal business model under carbon asset stranding constraints. Energy Policy, 149.

DAHL, R. E., LORENTZEN, S., OGLEND, A. & OSMUNDSEN, P. 2017. Pro-cyclical petroleum investments and cost overruns in Norway. Energy Policy, 100, 68-78.

ENERGY-FACTS-NORWAY. 2021. Electricity Production [Online]. Available: https://energifaktanorge.no/en/norsk-energiforsyning/kraftproduksjon/ [Accessed 30th April 2021].

EQUINOR 2020. Equinor Business Update December 2020. Equinor ASA.

FÆHN, T., HAGAN, C., LINDHOLT, L., MÆLAND, S. & ROSENDAHL, K. E. 2017. Climate Policies in a Fossil Fuel Producing Country: Demand versus Supply Side Policies. The Energy Journal, 38, 77-102.

GORDON, D. & FELDMAN, J. 2016. Breaking Down the Barrel: Tracing GH Emissions Through the Oil Supply Chain [Online]. Carnegie: Endowment For International Peace. Available: https://carnegieendowment.org/2016/02/09/breaking-down-barrel-tracing-ghg-emissions-through-oil-supply-chain-pub-62722 [Accessed 6th March 2021].

HOLDEN, S. 2013. Avoiding the resource curse the case Norway. Energy Policy, 63, 870-876.

HOLTSMARK, K. 2019. Supply-side Climate Policy in Norway. Nordic Economic Policy Review, 12, 209-235.

IEA 2020. World Energy Investment 2020. https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/ef8ffa01-9958-49f5-9b3b-7842e30f6177/WEI2020.pdf: International Energy Agency.

KENNER, D. & HEEDE, R. 2021. White knights, or horsemen of the apocalypse? Prospects for Big Oil to align emissions with a 1.5 °C pathway. Energy Research & Social Science, In Press.

KONKRAFT 2020. The Energy Industry of Tomorrow on the Norwegian Continental Shelf: Climate Strategy Towards 2030 and 2050. KonKraft.

KONKRAFT 2021. Framtidens Energinæring på norsk sokkel: Klimastrategi mot 2030 og 2050 Statusrapport 2021. KonKraft rapport 2021-2. KonKraft.

LIVSEY, A. 2020. Lex in depth: the $900bn cost of ‘stranded energy assets’. Financial Times, 4th February 2020

MUTTITT, G & Kartha, S. 2020. Equity, Climate Justice and Fossil Fuel Extraction: principles for a managed phase out. Climate Policy, 20:8, 1024-1042, DOI: 10.1080/14693062.2020.1763900.

MCKINNON, H., MUTTITT, G. & TROUT, K. 2017. The Sky´s Limit Norway – Why Norway should lead the way in a managed decline of oil and gas extraction. http://priceofoil.org/2017/08/09/the-skys-limit-norway-why-norway-should-lead-the-way-in-a-managed-decline-of-oil-and-gas-extraction/: Oil Change International.

MPE 2020. Longship – Carbon capture and storage. Med. St 33 (2019-2020) Report to Storting (white paper). Norwegian Ministry of Petroleum and Energy.

NILSEN, A. A., BOE, E. & LORENTZEN, M. 2021. Regjeringen flytter Equinor og Petoro til Næringsdepartementet: – Har jobbet med dette i over ett år [Online]. https://e24.no/boers-og-finans/i/6zmOVO/regjeringen-flytter-equinor-og-petoro-til-naeringsdepartementet-har-jobbet-med-dette-i-over-ett-aar: E24. [Accessed 23rd June 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021a. Exports of Norwegian oil and gas [Online]. Available: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/production-and-exports/exports-of-oil-and-gas/ [Accessed 26th April 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021b. Fundamental regulatory principles [Online]. Available: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/framework/fundamental-regulatory-principles/ [Accessed 6th May 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021c. The government’s revenues [Online]. Available: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/economy/governments-revenues/ [Accessed 26th April 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021d. Management of Revenues [Online]. Available: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/economy/management-of-revenues/ [Accessed 30th April 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021e. The Petroleum Tax System [Online]. Available: https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/economy/petroleum-tax/ [Accessed 26th April 2021].

NORWEGIAN PETROLEUM. 2021f. State organisation of Petroleum Activities [Online].https://www.norskpetroleum.no/en/framework/state-organisation-of-petroleum-activites/. [Accessed 10th May 2021].

NPD 2020. Power From Shore to the Norwegian shelf – Summary of report 2020. https://www.npd.no/en/facts/publications/reports2/report-archive/Power-from-shore-to-the-Norwegian-shelf/: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

NPD. 2021a. Plenty of oil and gas left on the Norwegian shelf [Online]. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jan/05/electric-cars-record-market-share-norway. Available: https://www.npd.no/en/facts/news/general-news/2021/plenty-of-oil-and-gas-left-on-the-norwegian-shelf/[Accessed].

NPD 2021b. Resource Report 2020 Exploration. https://www.npd.no/en/facts/publications/reports2/resource-report/resource-report-2020/: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

NPD 2021c. The Shelf 2020. https://www.npd.no/globalassets/1-npd/publikasjoner/sokkelaret/sokkelaret-2020/theshelf-2020-presentation-english.pdf: Norwegian Petroleum Directorate.

OSMUNDSEN, P. 1999. Risk sharing and incentives in Norwegian petroleum extraction. Energy Policy, 27, 549-555.

PELLEGRINI, L., ARSEL, M., ORTA-MARTÍNEZ, M., MENA, C. F. & MUÑOA, G. 2021. Institutional mechanisms to keep unburnable fossil fuel reserves in the soil. Energy Policy, 149.

PIGGOT, G., ERICKSON, P., VAN ASSELT, H. & LAZARUS, M. 2018. Swimming upstream addressing fossil fuel supply under the UNFCCC. Climate Policy, 18:9, 1189-1202.

PYE, S., BRADLEY, S., HUGHES, N., PRICE, J., WELSBY, D. & EKINS, P. 2020. An equitable redistribution of unburnable carbon. Nature Communications, 11.

REUTERS. 2020. Norway parliament grants more tax relief to oil sector | Reuters [Online]. Available: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-norway-oil-idUSKBN23F1NV [Accessed 26th April 2021].

REUTERS. 2021. Electric cars rise to record 54% market share in Norway. The Guardian, 5th January 2021.

SETO, K. C., DAVIS, S. J., MITCEHLL, R. B., STOKES, E. C., UNRUH, G. C. & URGE-VORSTAZ, D. 2016. Carbon Lock-In: Types, Causes, and Policy Implications. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41, 425-452.

STATISTICS NORWAY. 2020. Emissions to Air [Online]. Statisk sentralbyrå: Statistics Norway. Available: https://www.ssb.no/en/klimagassn [Accessed 25th January 2021].

TVINNEREIM, E., LÆGREID, O. M. & FLØTTUM, K. 2020. Who cares about Norway’s energy transition? A survey experiment about citizen associations and petroleum. Energy Research & Social Science, 62.

UNRUH, G. C. 2000. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy, 28, 817-830.

UNRUH, G. C. 2002. Escaping carbon lock-in. Energy Policy, 30, 317-325.

VAN DER PLOEG, R. 2018. Climate and the risk of stranded assets: portfolio management in Norway. https://nettsteder.regjeringen.no/klimarisikoutvalget/files/2018/01/Ploeg_klimarisiko_17January2018.pdf: Norway Climate Risk Commission.

VENABLES, M. 2018. New Oil And Gas Entrants Need New Funding Sources [Online]. https://www.forbes.com/sites/markvenables/2018/11/26/new-oil-and-gas-entrants-need-new-funding-sources/?sh=17f87cb278be: Forbes. [Accessed 10th May 2021].

VERGRAGT, P. J., MARKUSSON, N. & KARLSSON, H. 2011. Carbon capture and storage, bio-energy with carbon capture and storage, and the escape from the fossil-fuel lock-in. Global Enviromental Change, 21, 282-292.